By Christian Kile

https://newcriterion.com/blogs/dispatch/tone-poems

The essence of Gwen John’s art is summed up by her teacher James Abbott McNeill Whistler: tone. When her brother Augustus John talked about the character of her work, Whistler fired back, “Character? What’s that? It’s tone that matters. Your sister has a fine sense of tone.”

Whistler touched on something important. Gwen John’s penchant for more analytical methods, frequently returning to the same subjects, often emphasizing formal elements and with subtle variations, helps explain what makes her work so striking. Her paintings can convey a notion of “impersonality” or purity, a vital strand of modernism, more Continental in nature and closer to the maelstrom that came with the demolition of humanist optimism in the twentieth century.

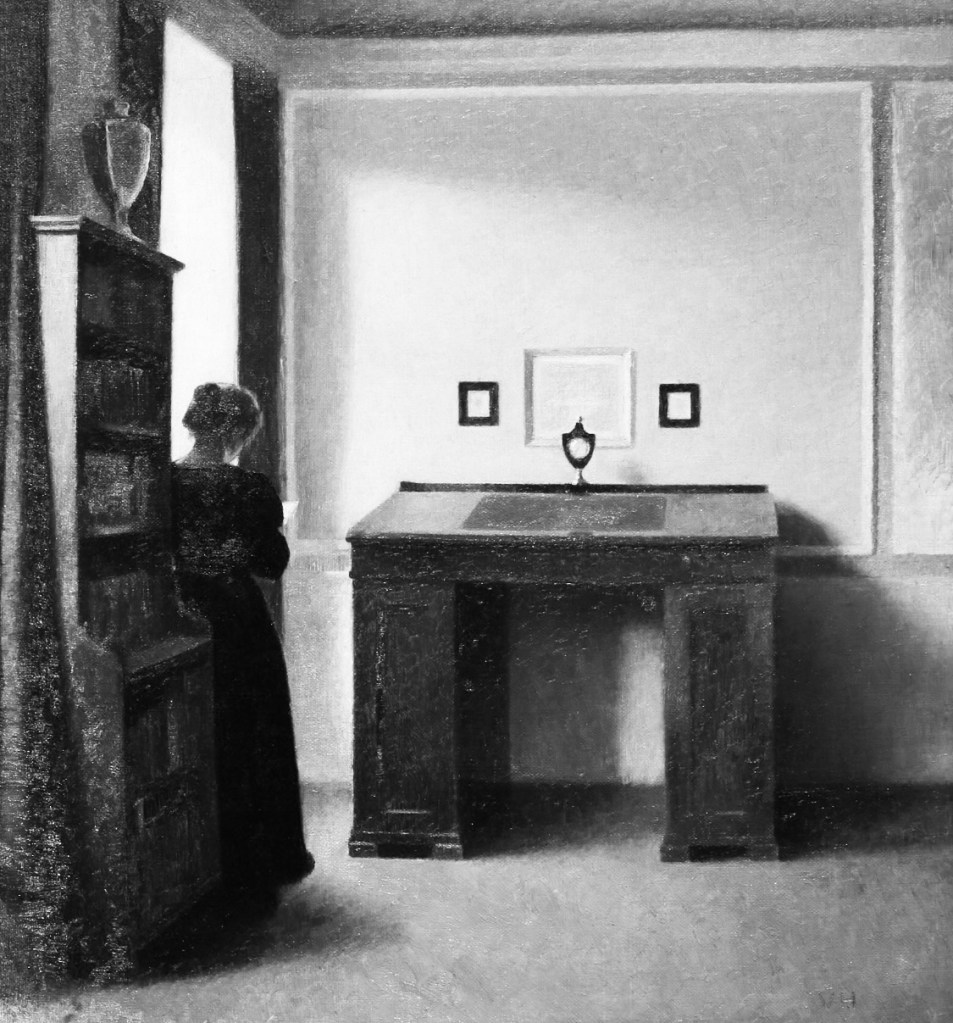

Drawing and painting were a habit from her early years, and the strength of her draftsmanship is on display from the first room in a new exhibition at Pallant House Gallery, “Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris.” This is the first major showing of John’s work in twenty years, with oils, works on paper, archival material, and personal possessions. The full course of her career is traced chronologically, and the exhibition includes a select group of works from her contemporaries. In the second room, Vuillard and a marvelous Hammershøi hang close by a selection of John’s interiors. In one corner there is a small-scale plaster head by Rodin, Head of Whistler’s Muse (ca. 1906), a monument to Whistler for which John modeled.

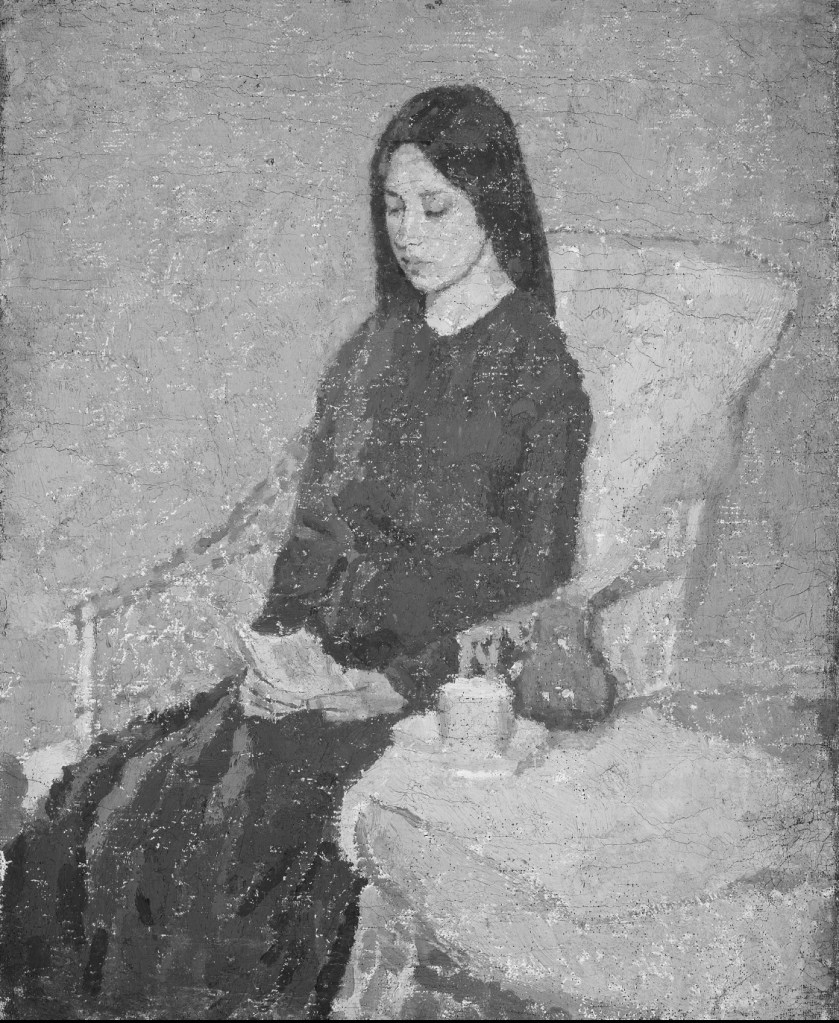

As the show progresses there is in John’s work an increasing economy of style: whether still life, portrait, or interior scene, images tend to be expressed with a more muted palette; colors lighten, diffusing into patches with little voids of finely primed canvas emerging through strokes of oil paint. Society figures are absent. Often subjects are anonymous female sitters positioned within a sparse studio interior as in The Convalescent (ca. 1923–24), The Seated Woman (ca. 1910–20), and Girl in a Mulberry Dress (ca. 1923).

Many compositions are repetitive in John’s drawings and paintings, sometimes highly so—the variations between images, often portraits, remain within a particularly narrow range. Seeing these works as reproductions does them few favors but viewing the originals hanging together, the nuances of the paintings achieve a satisfying effect, notably in one room where they sit comfortably opposite Cézanne’s oil painting Head of a Boy (1881–82).

“It is not unreasonable in Paris,” Paul Valéry observed, “to disguise what one has which is substantial and painfully acquired, under a lightness and grace which serve as a protection for the secret virtues of attentive and studied thought.” John’s art is often an embodiment of this insight. Despite her modest background, she established herself as an artist, becoming a recognized and respected figure in Paris during its modernist high tide. Following schooling at London’s Slade School of Fine Art, and further tuition under Whistler, she moved to France for good, living between the capital and its suburb of Meudon.

There on the continent, John found herself at a fountainhead of European modernism and became acquainted with many of its foremost figures: Picasso and Matisse, Braque and Wyndham Lewis, Brancusi and the poets Pound and Rilke. She became Rodin’s model and lover. It was a troubled affair, but, despite this he, like many others, esteemed her art.

This show does well to avoid focusing too much on John’s personal life as a means to understanding her art, rightly placing emphasis on her work. The once-overriding image of her as a recluse, apart from the avant-garde and intellectual currents of her time, is long gone. Given the marked increased focus on female artists in recent years, it’s surprising a figure this consistent has waited until now for a show of this standard.

The American lawyer and art collector John Quinn, an eminent enthusiast of John’s work, provided robust support, his period of patronage coinciding with her most prolific years as an artist (1910–24). He helped persuade John to part with her work as well as providing opportunities for her during wartime privations. Quinn said, “If I had to make a choice between the painting by you . . . and the Picasso, I should cheerfully sacrifice the Picasso.” Sometimes a little money and admiration are all that’s needed for encouragement.

During John’s final decade, her artistic pursuits apparently dwindled, and, due in part to illness, she became increasingly aloof and reclusive. Her work, however, remained desirable, and her family continued to offer support. The Brittany and Normandy coastlines were her retreat, and during a last visit to the sea she died in Dieppe at age sixty-three.

One leaves the show feeling John remains an underappreciated figure; putting this down entirely to her sex is unconvincing, for other twentieth-century female artists have gained much more notice. Without political diversions or manifestos, she knew her works were significant, and labored hard for them; perhaps she thought the personal cost too much and stopped her production early. Regardless of the cause, her self-imposed exile from the London scene and turn to Catholicism contributed to a body of work with an understated quietude. She reflected that for her, art came before children; who, she said, is remembered by history simply for becoming a mother?