By Christian Kile

http://www.sehepunkte.de/2023/10/38493.html

This ambitious study centres on a broad range of Francisco de Goya’s (1746-1828) work, along with its relationship to the elements of “modernity, Enlightenment, and critique.” (9) The author, Anthony Cascardi, concentrates on the artist’s paintings of polite society along with those mordant attacks on stupidity and cruelty in works such as the Caprichos and the Disasters of War, rejecting what he sees as the general view that it is mainly Goya’s darkest works which “establish his relevance for modernity”. (10)

Goya is presented as a man placed between an acutely backward Spain, lagging behind the more sophisticated civilisations of England, France and Germany which nonetheless also harbour the capacity to produce their own barbarity and limitations. Reacting to the forces of Enlightenment Europe and traditional Spain, Goya formed his project of “critique”, a technique that supplies to criticism a “self-conscious dimension that incorporates reflection on history, on tradition, on the underlying accepted categories and conditions of knowledge and belief, as well as on the medium through which these are represented.” (10)

The development of a secular nature in Goya’s work is introduced in the first chapter. His fresco, The Miracle of St. Anthony, with its stripped back religious elements, lack of a settled focal point for its subjects and its sky “vacant of anything heavenly”. (26) With his San Antonio commission that questions the traditional combinations of religious faith and painting technique, Goya may be seen as anticipating modernism, thus providing impetus for critical works probing both conventional methods of visual art and the world from which they supposedly came.

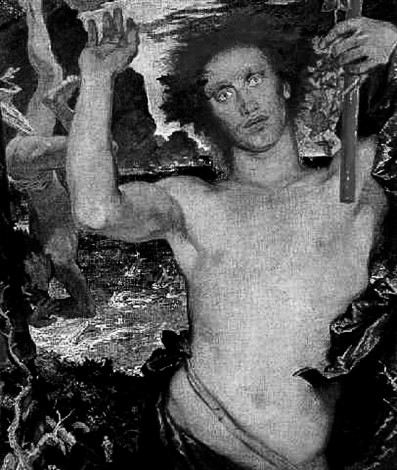

The critical strategy develops through Goya’s tapestry cartoons or large-scale oil sketches. Produced to convey “a distinctively Spanish social landscape”, certain of these works, despite their aspects of social harmony, are seen by Cascardi as including underlying elements of violence, “unsettling distortions of balance and perspective”. (55) There are intimations of the more biting images to come, like the Caprichos but Goya’s progressive political stance is somewhat repressed by the expectations of his court patrons.

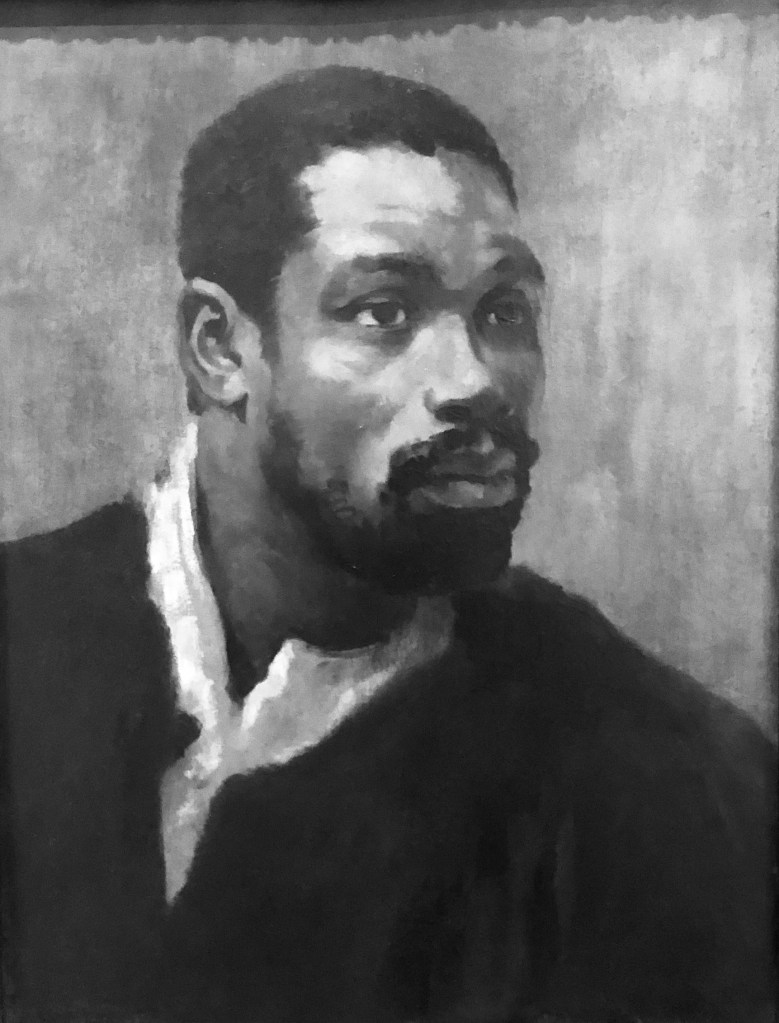

To further define Goya’s contribution to a modern art, one committed to figuration and an ardent critical approach, Cascardi compares the Spaniard’s work with readings of Édouard Manet’s Execution of Emperor Maximilian, Goya’s The Third of May famously acting as its model. Another of Manet’s great images, the Dead Toreador is presented as a work of aesthetic modernism, moving away from reference to the world, reflecting on itself and “being nothing other than what it itself presents, and not anything in the world.” (95) On the other hand, Goya, with The Third of May, paints with intense emphasis a concrete event, one manifesting apparent revolt at the actions of a French regiment. Here the famous lantern at once illuminates this scene, aiding artistic representation, but also allows the regiment to make their kill. Such is the bind that the Enlightenment finds itself in, argues Cascardi, where its rationality tends to produce its own special kinds of barbarism, despite shedding a world of superstition. Within The Third of May we are presented with Goya’s own critique, that of modernity’s own flaws. Cascardi finds this tension present in Goya’s portraits too; the painting of Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos at his Desk is said to portray a man dissatisfied by self-cultivation and a life of ‘good’ breeding. Neither are enough to stave off melancholy, boredom and scepticism.

Next, the Caprichos, an uncommissioned print series undertaken by Goya. Beginning with a self-portrait frontispiece, the remaining plates are split between the conscious or waking world, and that of nightmare. Between these two spheres, both producing their own kinds of horror, Cascardi provides some particularly engrossing readings of their text and images. The conventions of traditional perspective inherited from the Renaissance through to Velázquez give way to figurative wrenching and distortion, combined with the wit of Goya’s darkly comical captions. The critique element is seen to be born of the conviction that self-deception and virtually every other shortcoming are rife, and new methods for presentation of the world must be realised to divulge it. Critique is here defined by Cascardi as “a reflection on the limitations of the conventions of representation, including the difficulty involved in isolating a position within the social world from which to see the truths that society endeavors to hide.” (145)

Goya’s attitude towards secularization is developed further in a chapter contrasting him with the German philosopher Kant, described by the author as “wedded to the idea of reason’s autonomy […] he presupposed the irrelevance of the preexisting contexts of belief–contexts that reason saw itself as having successfully overcome.” (190) Goya, on the contrary, made works which graphically expressed reason’s failure to achieve this Kantian design, continuing to be dogged by antiquated and base tendencies. Moreover, it could not supply an alternative salvation comparable with religion.

Goya is portrayed as an artist who feels something is terribly wrong with his world, and something ought to be done about it, but all he can do is make art about the spectacle. As Cascardi asserts, when considering Goya one should bear in mind that he challenged “the idea that any single framework of principles can underwrite the whole of cultural life.” (228)

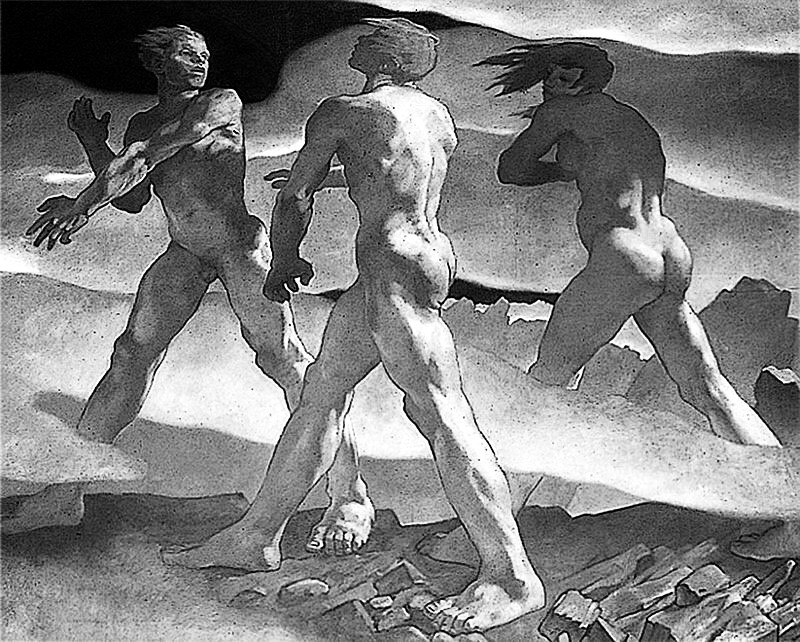

With the Disasters of War Goya switches his gaze to “historical events” rather than the “social ones” of the Caprichos, events dealing with the most extreme violence. These works conjure both a vivid impression of wartime suffering, its mutilation and repercussions. The argument for Goya’s attitude towards Enlightenment’s deficiencies resurfaces, evidenced by French aggression, whilst the inability to turn back to a reactionary life associated with Spanish history make each unbearable in its own way. This impasse “contributes to the sense of cultural and historical dislocation in the Disasters.” (237)

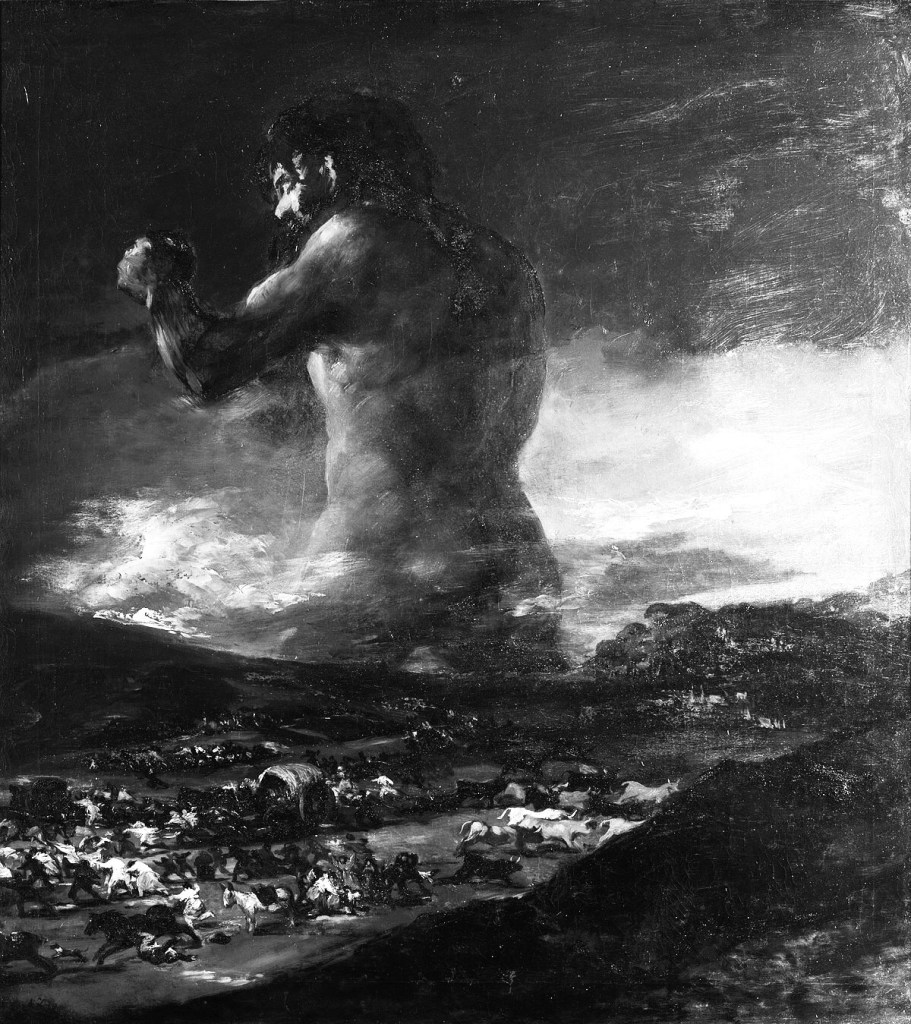

Cascardi’s book complements the substantial list of earlier scholarship on Goya, through a blend of art history, intellectual history and the wider humanities. The volume integrates insights from major thinkers, expressly those of Kant and prominent writers on Goya, including Janis Tomlinson, Fred Licht, and Robert Hughes. [1] The discussion of the relationship between Goya’s tapestry cartoons and later works is especially absorbing, such as the comparison between, at first glance, the buoyant and refined Blind Man’s Buff [sic] and the crude state of aggression in the Black Painting, Duel with Cudgels.

Darkness is a word chosen frequently to describe Goya’s work. When he brilliantly exposes self-deception, wilful ignorance and corruption, it is not political,in the sense that no matter who is in charge, flaws remain, often horrifying ones, regardless of whether the artist finds a way of ‘out enlightening’ the Enlightenment.

Despite Goya’s respect and sympathy for the talents and actions of a few individuals, it is difficult to see the artist offering a panacea for the ills he pictured so mercilessly. Along with Cascardi’s admiration for the critical element of Goya’s nature, he chooses to close his chapter about the Black Paintings on a utopian note, where we encounter the author’s own bias or ideology. Throughout the book’s notes the thought of figures associated with the student upheavals of the sixties, thinkers like Althusser, Adorno, Barthes and Derrida, appear. The wide and varied range of texts contributing to Francisco de Goya and the Art of Critique suggests Goya lends himself, perhaps exceptionally, to extensive speculation, and in the case of this book prompts as much interest in the ideas of the author as its subject.

[1] Janis Tomlinson: Francisco Goya y Lucientes, 1746-1828, London 1994. Fred Licht: Goya: The Origins of the Modern Temper in Art, New York 1979. Robert Hughes: Goya, London, 2003.